Somehow, I managed to make it to my 30’s before I heard of Colonel Jeff Cooper’s safety rules. That included enlistments in the 6th Marines Infantry, the Army 19th SFGA and the Army 18th Engineers as a medic. So, I had spent a fair amount of time carrying around things that go bang for Uncle Sam with no mention of the man who created these four pillars of gun safety.

To be honest, my first reaction was they just didn’t make sense as rules for combatives. They sounded more like range rules some lawyer dreamed up.

But in the 1990’s Jeff Cooper had a following Jim Jones or David Koresh would’ve killed for.

The point being, no one messed with Jeff. Especially not aspiring young handgun instructors trying to develop a reputation for themselves. So like everybody else, I toed the line.

Cooper earned the respect he got. He had a knack for observing and analyzing things that were previously undefined and giving them a new context.

One of the things he tackled was creating a set of rules that helped keep people safe when guns are being handled. And his rules do that very well.

But… There’s more to it than that.

Two Kinds of Danger. Two Kinds of Safety.

There’s the potential danger we can pose to ourselves and others based on how we handle a gun. This is managed through Technical Safety measures.

But let’s not forget the reason we carry a handgun in the first place – to protect ourselves and others from the potential dangers posed by those with ill-intent. This is managed with Tactical Safety measures.

Cooper’s rules come up short for those.

Heresy, you say? Let’s go through each of Cooper’s safety rules, taking his verbiage at face value, and see how each one measures up against both safety concerns. After each evaluation, I’ll share our adaptation of that rule.

![]() Cooper’s Rule #1 – All guns are loaded.

Cooper’s Rule #1 – All guns are loaded.

That may have been an appropriate assumption if you’re going to a Leatherslap competition in 1959. But it’s not exactly the mindset you need when training for the street in 2023.

On the range, it’s safe to treat every gun is if it’s loaded, because if you’re wrong, the worst thing that happens is you get a click instead of a bang. But paper targets don’t carry knives or shoot back. On the street, that “click” is going to sound a hell of a lot louder than the bang you were expecting.

Making the wrong assumption about your gun’s status on the street could get you hurt.

No Solder or Marine would head onto a battlefield and no cop would go on-duty assuming their gun is loaded. They would confirm it’s loaded.

The same should apply to concealed carrying civilians.

If anything, we take extra time when doing an administrative load. The first load of the day is our opportunity to double-check everything. We confirm a round is chambered, the slide is completely forward and in battery, we give the mag a quick tug to make sure it’s properly seated.

Our rule #1 – Always confirm the status of your gun is appropriate for your intended use.

![]() Cooper’s Rule #2 – Never point your gun at anything you don’t intend to destroy.

Cooper’s Rule #2 – Never point your gun at anything you don’t intend to destroy.

Once again, the concept is great for a range rule, but a bit too absolute for the street.

It is not unreasonable to imagine a street situation where the lesser of two evils could be to sweep your muzzle past an innocent to stop a greater threat to more people.

Frankly, this rule has been taken to ridiculous extremes.

I was in the infantry. We spent 40 hours a week pointing guns at each other. We called it practice.

How about gun stores, where people handle guns like grocery store produce. No thought of muzzle discipline, and no big concern.

What about parades and ceremonies where real guns are used to pay tribute.

I actually heard an NRA Regional Training Counselor say that we shouldn’t even point Blue Guns at each other.

It’s not just absurd. It shows how the ridiculousness of political correctness has become as pervasive in the firearms industry as it is everywhere else.

We don’t encourage it. We look for every opportunity to avoid it. We never take it lightly. But we don’t categorically reject it either.

Instead of convincing ourselves to not even consider the possibility that innocents could be put at risk from a line of fire we’ve been forced into, then finding ourselves unprepared for a situation where we have no choice, we should make these risks and the corresponding safeguards and alternatives to such a possibility part of our ongoing training.

Our Rule #2 – Never point your gun at anything you can’t justifiably put at risk.

![]() Cooper’s Rule #3 – Keep your finger off the trigger until your sights are on the target.

Cooper’s Rule #3 – Keep your finger off the trigger until your sights are on the target.

I actually heard Col. Cooper contradict himself on this. He stood in front of a class and said “As I start to raise my gun, I move my finger to the trigger, so I can break the shot as soon as I get on target.” And that makes total sense!

We do everything we can to shave fractions of a second off our draws and hundredths off our splits. Why would we train combative students to wait until they have a proper sight picture before moving their finger to the trigger.

That’s not how we train to shoot strings of follow-on shots. And it’s not how we train to shoot on multiple targets.

We can come off the trigger in a way that’s both technically and tactically safe, without disrupting our grip on the gun or adding to the time it takes to get on target and break a shot.

Our Rule #3 – Keep your finger off the trigger until your gun is oriented where it’s tactically safe to do so.

![]() Cooper’s Rule #4 – Be sure of your target and beyond.

Cooper’s Rule #4 – Be sure of your target and beyond.

Cooper’s 4th Rule shows a lot of insight. He’s saying make sure you’re shooting at the right thing. And just in case you miss or over penetrate, be mindful of what’s behind it.

But, we need to apply that basic idea a bit more broadly.

It’s almost a foregone conclusion that if you are ever forced to shoot, you will in all likelihood, have to account for the possibility of friendlies either between, around or behind you and/or your attacker(s).

Any decision to shoot must be based on what you know your capabilities are.

What do I mean by that?

In combatives, no one has the right to “shoot and hope for the best”. We don’t get to protect ourselves at the expense of the safety of innocent bystanders. That’s the deal you make when you decide to strap on a gun and go out into the world.

That means we may need to limit what we attempt to do when protecting ourselves.

We can’t just shoot as fast or as far as we can, like a soldier laying down suppressive fire. We need to know where our rounds will hit and if we don’t know for sure, we don’t take the shot. It is genuinely shocking how many experienced shooters don’t understand and accept that as the a fundamental standard.

Finally, I have never heard an instructor talk about how we must be aware of where we might be drawing fire to.

Once again, most of us go down to our local “bullet bowling alley” and fling rounds down a 3-foot wide, 25-yard long piece of real estate we’ve rented for an hour.

Any notion of movement, angles, or “No-Shoot” obstacles never even crosses our mind.

So, what do we end up learning? We get really good at shooting at an indoor range – nothing more.

Our Rule #4 – Be aware of what’s at, around, beyond and between you and your target.

Ahh. The “Big Boy” Rules

Safety rules shouldn’t be thought of as something we only use when we’re training. They’re not just safety rules. They’re engagement rules.

Some may say I’m splitting hairs over verbiage. I’m not saying Colonel Cooper wasn’t aware of the things I’ve talked about here. I don’t know. I never had a chance to sit down and talk with the man.

But decades after he codified his rules, very few have openly addressed the tactical safety risks associated with combative shooting. Instead, there’s this underground code (most likely controlled by the Illuminati) called Big Boy Rules.

This is when instructors, who know the secret handshake, are sure they’re not going to show up on Instagram or YouTube, come clean about the rules we really use that break the other rules.

So we’ve ended up with one set of rules we talk about in the open and another set of contradicting rules we hide like a bad habit.

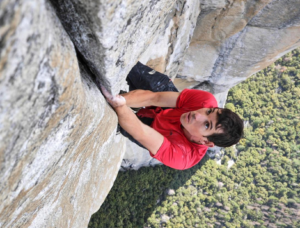

It’s time to forget about political correctness and stop placing liability concerns over true safety. This isn’t soccer camp. We’re talking about armed combatives for the street. It can be a dangerous exercise. But so can skydiving, dirt-biking, rock climbing and a hundred other things.

If Alex Honnold wants to climb all 3,600 feet of El Cap without a rope, they invite him to give a TED Talk. But if a handgun instructor suggests that one way to retain control of your weapon is to grab the front half of your slide, asteroids laced with some damned fried chicken virus start raining down on elementary schools in minority neighborhoods.

Let’s be thoughtful. By all means, let’s be administratively safe. But let’s also keep our training meaningful, interesting and fun by exploring all aspects of training for reality.

Nothing I’ve said here is meant to be critical of Col. Cooper. He was a fellow Marine and it was his perceptiveness that prompted my own thoughts on the matter. While I stand by my arguments, I acknowledge that we’ve come to these improvements by standing on his shoulders.

Semper Fi, Jarhead.

Rick Molina